(sólo en inglés)

Photos by the Author (except the anemone)

Poetry is my mother tongue which I learned in the corners of my cradle.

Poetry gives me words extracted from my chalk quarry under the tenuous shell of days, and the rational reason, the complicated speeches, the endless bursts of hypocritical voices… It allows me to share more emotion, emerging through our experiences and going far beyond our senses.

This lapidary language digs and dissects the thought, reaches signs stimulated by calls to external excavation, to the perpetual need to trace a path in the vocabulary and move forward, exist for oneself and for others, and share even more whatever we can find with our own fingers, endlessly.

“This was a bit of happiness that I had picked up at the edge of a ditch” (lyrics from a song of Félix Leclerc). Here, it is a cocoon, from which a living being with six legs (thus an insect) has emerged a few days later: the famous small emperor moth (eudia pavonia in latin), a 6 cm female.

Its cousin, the giant peacock moth (saturnia pyri) with a wingspan of 12 cm, lives not that far, in our region. Despite their similarities, there is no possible confusion.

This is the large night peacock drying itself on blackthorn after emerging from its cocoon. It is a copy of the lesser peacock but twice as big. These insects are native to our region.

Both species are endangered due to the destruction of their natural habitats (shrubs, old orchards, hedges), among other reasons.

Mating of small emperor moth in the author’s hand

There is no lepidopteran as spectacular as the peacock moth in its sexual behaviour. The naturalist Jean-Henri FABRE explains it in his book “Souvenirs Entomologiques”, Volume VII, Delagrave Editions.

He is the first self-taught scientist who memorized and accurately transcribed many observations, spending 32 years of his life to carefully watch insects in nature, including these butterflies, demonstrating through experiments the reality of the attractive effluvia that circulate between the sexes.

His universal and brilliant novels on wildlife are serious references for Nature enthusiasts and professionals.

The talented botanist and Senior Lecturer at the MNHN (National Museum of Natural History) Yves DELANGE is his biographer.

This incredible discovery of the effluvia did not appear in scientific literature until 68 years after J.H. Fabre, in 1959.

It inspired perfume manufacturer who tried to duplicate effluvia chemically and to integrate them in their bottles as a seduction tool.

In fine weather, it is therefore possible to watch this non-migratory butterfly, which moves around as soon as the weather gets milder.

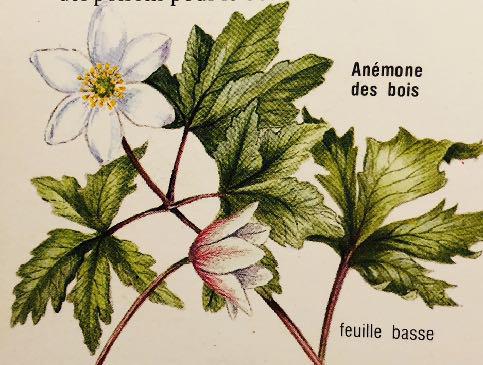

Photo on the right: The wood anemone, Sylvie anemone, flowers in the undergrowth, just before the leaves grow on the trees, because it needs sunlight to blossom in spring. It is one of our first wildflowers along with the primrose and the violet.

Why are these small lively animals rushing from everywhere in March? What is this mystery?

Who is letting them know that their sexual partner is waiting for them a few miles away? There are actually chemical messages, sexual hormones called pheromones, carried by the wind, showing them the way.

Carrying ovaries, the rather heavy nubile females are hardly flying and stay waiting, flapping their wings, until the males coming from the sky would land on them, quite often in an uncomfortable position.

The long mating lasts for several hours at the end of a sunny day, with frenetic and noisy vibrations, preferably in a light north-east wind.

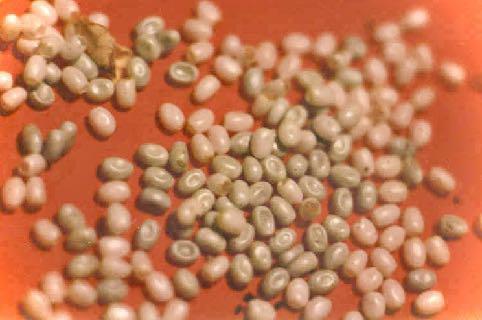

Two days later, about a hundred of brown eggs are laid in sleeves, at a pace of one per minute, in a bundle glued around the stems of a blackthorn, the plant-host of the future caterpillars, which the female recognises thanks to its sense of smell, as it is linked to this plant by its specific genetic code.

The eggs of the «small emperor » butterfly

The colouring of the eggs hides them from the stomachs of birds and bugs, which are their predators. They hatch about twenty days later if the weather conditions are favourable.

The blackish caterpillars, with their herd mentality, are rapidly starving at birth and feed only on imparted leaves and nothing else: they are phytophagous.

When they emerge from their eggs, food is immediately available for them.

They eat for two and a half months, then each one of them encloses itself in a natural silk cocoon they had woven.

Unbelievable fasters, the small emperor moths live for about fifteen days with the unique mission to breed and ensure the survival of their species.

A female night peacock dries on the author’s hand

Unlike butterflies, which produce two generations per year, the emperor moths only produce one, as their life are too short.

This “ephemeral native” is a fine example of self-sacrifice. I have been watching it closely for many years in my breeding farms, and I can tell its elegance and its communicative freshness delight the senses right before nightfall.

See you in May for the continuation of this story.

With the authorization of l’Est Eclair / Libération Champagne